Ten years-ago I bought a left-hand-drive Peugeot on French eBay. I flew to Brittany, picked up the keys from the Ryanair desk, and found the car parked in Long Stay. Having driven back to the UK and formally imported the vehicle my wife confirmed her view that a three-week sojourn driving to Banjul, Gambia was in fact an expensive holiday without her and the kids. The trip was abandoned. I sold the Peugeot to man who’d left his wife and gone to live in France.

In November 2011 I drove to Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, being among the last ‘tourists’ to stay in Lawrence’s room at The Baron’s Hotel, Aleppo, before the tragedy of the war fully unfolded.

Fast-forward to 27 December 2018 and I was on my way again, heading to Walthamstow to pick up a co-driver I had never met, for a journey down West Africa to Bamako. The route would take three to four weeks. We’d be driving a 2003 ex-British Transport Police 4×4, another eBay purchase and my family’s faithful transport for several years.

Eugene, my co-driver, had suffered a very recent heart attack and stroke, followed by triple bypass surgery. By cruel coincidence at the same time his brother had also suffered a catastrophic cardiac event, from which he was expected to die while we were in Africa.

I’d never envisaged a fund-raising aspect to the journey, save for the final auction of the car in support a primary health care clinic outside Bamako. Eugene, having been given a second chance at life, was determined to give something back. I was happy to go along, petitioning friends and business colleagues to donate via a GoFundMe page.

The journey

Here’s a photo essay from the journey, 5,500 miles that included tedium, fatigue, sublime beauty, despair and worrying excitement. I’d do it all again.

Newhaven to Dieppe 28th December 2018. A last view of Britain for almost a month. Thanks to DFDS Seaways for providing our passage.

France was unrelentingly flat and foggy until rare rays of sunshine broke through at Biarritz. It was still freezing. Hats off to these brave swimmers.

Valladolid, our first night in Spain. Excellent tapas and tinto at Meson D’Enrique.

New Year’s Eve in Jerez della Frontera. Everywhere was closed saved for a down-at-heel Chinese café and even they chucked us out before midnight.

1st January 2019. Under trees laden with oranges, free parking in Jerez, for one night only.

Chefchaouen in Morocco’s Rif Mountains. Having tumbled onto the Algeciras to Ceuta ferry, after a lengthy wait at Morocco customs, it was a winding 90km drive in darkness up into the Rif. On arrival I managed to pick up a 300 Dirham fine for not wearing my seatbelt – you had to be there, it was harsh.

Coffee stop half way to Fez. The car had started to leak diesel by this point, but despite close examination I couldn’t work out where it was coming from.

Marrakech was a city that excelled in industrial tourism. A heartless hospitality abattoir that sees plane loads of new arrivals delivered to the night market of Djemaa El Fna. Here, they’re humanely stunned by otherness before having their wallets eviscerated by razor sharp shysters.

‘Here’s one I prepared earlier.’ Marrakech’s Djemaa el Fna.

It was a relief to reach the fresh mountain air of the High Atlas, en route to Tizi n Test’s 2,100m pass.

Though there were some wrong turns…

Back on the right road. A classic High Atlas village.

Farther south, Western Sahara is a disputed territory. The western coastal strip has been annexed and increasingly assimilated by Morocco. The eastern third is controlled by the self-declared Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. A UN-backed independence referendum, promised in 1992, has yet to be held.

In 2016 more than 70 UN personnel were expelled by Morocco from the portion of Western Sahara it controls. UN military observers (MINURSO) are still much in evidence.

Long days driving parallel to the Atlantic characterised Western Sahara. Often the only accompaniment was an incongruously commercial Spanish radio station drifting across from the Canaries, some 60 miles off shore in the Atlantic.

Tea stops broke up the long days of driving

The Western Saharan town of Dakhla is an oasis of activity. A real relief after the unrelenting desert. Bizarely, it’s also a kite surfing mecca.

A night at the border, waiting to cross into Mauritania next morning.

No man’s land between Western Sahara and Mauritania. The end of the road for some…

We’ve left Western Sahara. This rough, sandy track is rumoured to lead through a mine field to the Mauritanian frontier.

Nouadhibou, the first town in Mauritania, was initially difficult to penetrate. Fatigue, combined with accrued stress.

The oasis of Chez Ali’s camping compound came at the right time after the long day crossing the border from Western Sahara.

The road south to Nouakchott was sometimes difficult to discern.

Nouakchott seemed at first unsympathetic – no more than a necessary stop for visas, and for Eugene a chance to be very ill indeed. However, growing accustomed to our neighbourhood’s sandy streets, its appeal grew.

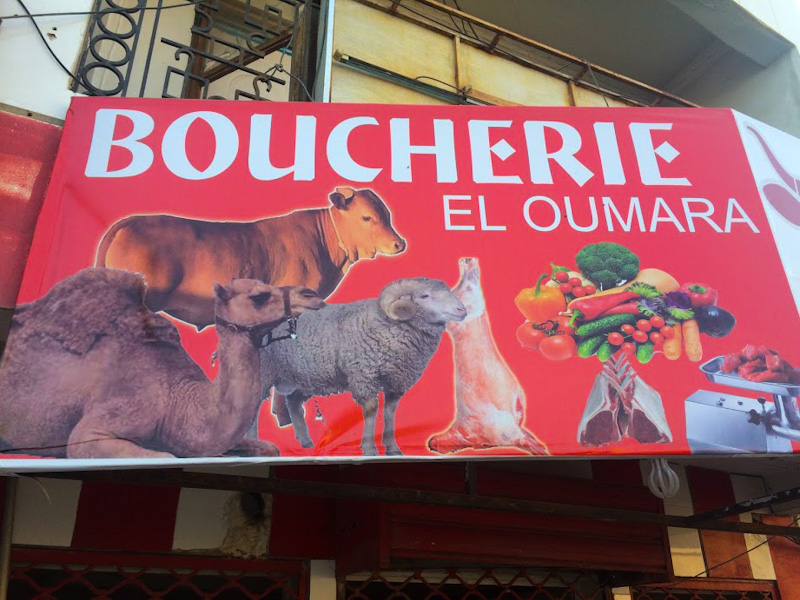

This butcher’s shop also doubled as a local bureau de change.

250km east of Nouakchott, this is the go-to-guy for a smart suit in the town of Aleg.

Conceal and reveal. They don’t get many tourists in Aleg. We received nothing but smiles and best wishes. However, in 2007 four french overlanders were murdered by Al Qaeda while having a picnic just outside town.

East of Aleg, this small Mauritanian village had no café. A shopkeeper made us a version of Nescafé au lait himself.

A tea stop and a chance for Eugene to take his meds on the way through Kiffa, Mauritania.

Buying insurance, part way through the interminable border crossing from Mauritania to Mali. At the final bureaucratic hurdle, and losing the will to live, having purchased the necessary ‘laissez passer’ I must have placed the car’s entire catalogue of documentation on the roof, before getting in and driving off into to the night. Fortunately, I had digital copies of the most important V5 logbook.

Nioro du Sahel, our first overnight in Mali. We really felt as though we’d finally arrived in Africa, despite having travelled through the continent for three weeks. As far as getting to Lake Manantali, we couldn’t have been more wrong…

These fellows joined us for our roadside lunch on the way to Kayes – ‘the hottest town in Africa.’

Baobab trees, hornbills, lilac-breasted rollers, combined with the human energy Malian towns emphasised just exactly where we were.

Travelling overland, surroundings and people change incrementally. However, by the time we reached Mali the changes were speeding up. This is the tiny village of Dialafara.

Leaving Kayes, we stopped to lend tools to a broken-down minibus, hoping, should we need it, that karma would be repaid. I’m not entirely convinced it was. Over the next 300km of pistes we needed all the help we could get.

The Nissan was pretty tough, and did far more than I ever expected. However, hitting a tree stump resulted in an involuntary overnight by the side of the piste – the ‘road’ having ceased hundreds of kilometres previous. A forgotten bottle of Moroccan red wine temporarily diluted the despair.

We were remote but not isolated. In the morning a young boy from a nearby cluster of huts brought help. Bush mechanics are not like the rest of us. Their minds are wired differently. Arriving on the back of a scooter with a small sack of tools that resembled Mediaeval weapons Fedro’s ingenuity got us moving again. At least until the next tree stump.

After three days and over 300km of the most unrelentingly rough pistes I’ve ever encountered we finally made it to Manatali. Here, in the town’s only restaurant, Madame Saffi prepares Oeufs Surprise (a variation on scotch eggs) for our celebratory supper, and plans how best to overcharge us.

We stayed at Casper Jansen’s idyllic Cool Camp, overlooking the Bafing River. Swimming in the river was restorative, though it was advisable to look out for hippos before diving in. Casper generously showed us around town, helped us sort out destroyed tyres, and orchestrated the fixing of a further diesel leak. He was among the friendliest and most generous people that we met. Do call by his place if you’re passing through.

Cool Camp’s guest accommodation. We decided it was ‘a luxury lodge without the luxury.’ It suited us very well.

Filling up before leaving Manatali. We were promised 98km of rough track before silky smooth tarmac for the last 100km to Bamako.

Crossing the Niger and arriving into Bamako

Bamako’s artisan market proved a concentrated dose of human industry.

All his own work.

Other products were less beautiful.

Elsewhere in Bamako these boys were having a great contest. Notice the rocks they’re standing on.

Kansas it ain’t.

At long last Bamako provide an opportunity to sort those nagging ailments that had dogged us throughout the trip.

Handing over the Nissan keys to the splendid Sunny Akuopha of Bamako Rotary Club. It was later auctioned, raising 800,000CFA (~£1,068) to directly support primary healthcare provided at the Eden Clinic, Dinfara – 120km outside Bamako.

In conclusion

It was clear from the outset our personalities, strengths and weaknesses were different. I’d like to say our attributes were complementary. At times we laughed. At times we argued. At times we were supportive. However, that the journey was concluded without one of us intentionally killing the other was at least as much of a triumph as reaching Bamako itself.

In the end we raised over £6,000 for the British Heart Foundation, NUJ Extra and the Journalists’ Charity, and over £1,000 for the Eden Clinic in Mali.

Thanks to our sponsors

- Bradt Travel Guides (pioneering guides to exceptional places since 1974)

- DFDS Seaways (good value ferries to France and Holland)

- Land Rover Explore Outdoor (ultra-rugged phones for hikers, bikers and trekkers)

- Kamageo (the leading marketing and representation agency for African tourism)

- Spotty Dog Signs + Print (digital signs, stickers and logos)

- The Narrow Nick (My preferred waterhole in Rothbury, Northumberland)

- Undiscovered Destinations (ground-breaking adventure travel in the world’s most exciting regions)

- And all those hundreds of generous private donors